With less than 10 years until the 2030 deadline for achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), governments need to step up their efforts to meet global food security and environmental targets, according to a new report released today by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Although progress towards the SDGs is expected to be made in the coming decade – assuming a fast recovery from the global COVID-19 pandemic, and stable weather conditions and policy environments – the past year of disruptions from COVID-19 has moved the world further away from achieving the SDGs. This calls for urgent attention to the factors and forces driving performance in agri-food systems.

The OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030 provides policy-makers with a consensus assessment of the ten-year prospects for 40 main farm and fisheries products at regional, national and global levels, analysing the drivers of performance in the agri-food markets and helping to inform forward-looking policy analysis and planning. The Outlook baseline projections describe expected trends based on existing policies, highlighting areas where additional effort is needed to meet the SDGs.

Ensuring food security and healthy diets for a growing global population will remain a challenge. Global demand for agricultural commodities – including for use as food, feed, fuel and industrial inputs – is projected to grow at 1.2 percent per year over the coming decade, albeit at a slower annual rate than during the previous decade. Demographic trends, the substitution of poultry for red meat in rich and many middle-income nations, and a boom in per capita dairy consumption in South Asia are expected to shape future demand.

Sustainable productivity growth is key

Productivity improvements will be key to feeding a growing global population – projected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030 – sustainably. Of the increases in global crop production expected in 2030, 87 percent are projected to come from yield growth, while 6 percent to come from expanded land use and 7 percent from increases in cropping intensity. Similarly, a large share of the projected expansion in livestock and fish production is expected to result from productivity gains. However, herd enlargement is also expected to significantly contribute to livestock production growth in emerging economies and low-income countries.

Trade will continue to be critical for global food security, nutrition, farm incomes and tackling rural poverty. On average across the world, around 20 percent of what is consumed domestically is imported. Looking ahead to 2030, imports are projected to account for 64 percent of total domestic consumption in the Near East and North Africa region, while Latin America and the Caribbean region is expected to export more than a third of its total agricultural production.

“We have a unique opportunity to set the agri-food sector on a path of sustainability, efficiency and resilience,” OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann and FAO Director-General QU Dongyu said in the Foreword to the Outlook. “Without additional efforts, the Zero Hunger goal will be missed and greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture will increase further. An agri-food systems transformation is urgently needed.”

Global greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are projected to increase by 4 percent over the next ten years, mostly due to expanding livestock production. This is despite the fact that emissions per unit of output – carbon intensity of production – are expected to decrease significantly over the period.

Globally, aggregate food availability is projected to grow by 4 percent over the next decade to reach just over 3000 calories per person per day. Per capita consumption of fats is projected to grow the fastest among major food groups, due to higher consumption of processed and convenience food and an increasing tendency to eat outside the home, both associated with ongoing urbanisation and rising women’s participation in the work force. Income shortages and food price inflation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic are reinforcing this trend.

In high-income countries, per capita food availability is not foreseen to expand significantly from its already high levels. However, income growth and changing consumer preferences will support the shift away from staples and sweeteners to higher-value foods, including fruits and vegetables and, to a lesser extent, animal products.

In low-income countries, food availability is projected to increase by 3.7 percent, equal to 89 calories per person per day, mainly consisting of staples and sweeteners. Economic constraints will limit increasing consumption of animal products, fruits and vegetables. Due to income constraints, the per-capita consumption of animal protein is projected to decline slightly in Sub-Saharan Africa, a region whose self-sufficiency for major food commodities is, on current trends, expected to decrease by 2030.

Over the medium term, weather, economic growth and the distribution of income, demographics and shifts in dietary patterns, technological developments and policy trends will shape food and agricultural prices. While the FAO Food Price Index has risen strongly in the past year, these increases are expected to be followed by a period of downward adjustment. The Outlook projects that food prices will resume a gradually declining trajectory in real terms, consistent with slowing demand growth and expected productivity gains.

While the Outlook focuses on medium-term trends, a wide range of factors can generate the conditions for short-term price fluctuations in agricultural markets. For instance, developments in energy markets, which affect input prices, and the greater volatility in grain prices associated with the increasing market share of some countries, contribute to the differences between projected and observed prices.

More information on the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook is available here. For further information or interviews, journalists are invited to contact Lawrence Speer in the OECD Media Office (+33 1 45 24 79 70).

Working with over 100 countries, the OECD is a global policy forum that promotes policies to preserve individual liberty and improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world.

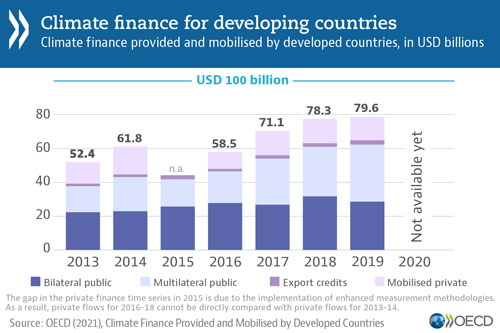

“Climate finance continued to grow in 2019 but developed countries remain USD 20 billion short of meeting the 2020 goal of mobilising USD 100 billion,” OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann said.

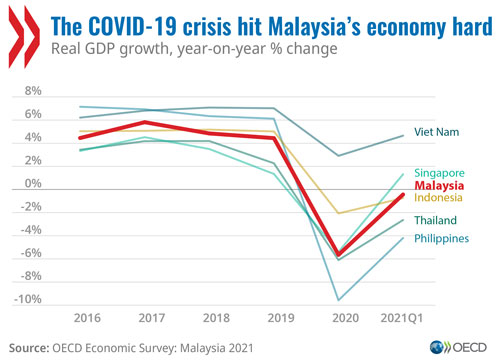

“Climate finance continued to grow in 2019 but developed countries remain USD 20 billion short of meeting the 2020 goal of mobilising USD 100 billion,” OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann said. The economic blow from COVID-19 hit small firms and young, self-employed and migrant workers hard. Persisting high unemployment underscores the need to improve social protection and policy support for those not adequately covered, including many independent employees working for online platforms, and the micro-, small- and medium-sized businesses that account for a significant part of Malaysia’s economy.

The economic blow from COVID-19 hit small firms and young, self-employed and migrant workers hard. Persisting high unemployment underscores the need to improve social protection and policy support for those not adequately covered, including many independent employees working for online platforms, and the micro-, small- and medium-sized businesses that account for a significant part of Malaysia’s economy.