Remarks by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB, at the Forum Villa d’Este, Cernobbio, 1 September 2017

In my remarks today, I will reflect on the outlook for growth in the euro area taking distance from monetary policy considerations at the present time by focusing on recent economic developments and their structural component. I will then elaborate on opportunities and risks posed by broad structural developments across euro area countries.

In my intervention today, I want to convey five main messages:

First, the ongoing cyclical recovery in the euro area is now broader and more consolidated.

Second, this notwithstanding, the strong worldwide reflationary phase that seemed likely at the beginning of the year has not materialised. Therefore, the tasks of normalising inflation and unemployment to acceptable levels continue to be difficult.

Third, the euro area peripheral countries have completed a notable adjustment phase. Consequently, the monetary union is now more resilient to shocks as a result of a reduction in imbalances and stronger synchronisation of the economic cycle across countries. The euro area is thus better prepared to resist financial market shocks.

Fourth, in this context, a correction in the worldwide risk premia, particularly in the bond market seems now more absorbable. Financial conditions may nevertheless deteriorate suddenly, due to developments in the US or emerging economies’ or to geo-political risks that can trigger spikes in a situation of prolonged low volatility.

Fifth, resuming real economic convergence among member countries is vital for the euro area. This is the next fundamental challenge and it will require more structural and institutional reforms both at national and European levels.

A broader and more consolidated recovery

The euro area has now been expanding for 17 consecutive quarters while business confidence is at a decade high. Equally important, practically all countries are now taking part in the recovery and more people in the euro area are employed today than before the crisis. These developments would not have materialised without the ECB’s expansionary monetary policy after the second recession in 2012-2013.

While we can be increasingly confident about the sustainability of the recovery, we have to recognise that it has taken much longer for the euro area than for other advanced economies, to emerge from the financial crisis which started in 2008.

The depth and length of the euro area crisis unveiled inter alia the incompleteness of the euro area’s institutional design. However, on the positive side, it has also encouraged the euro area to equip itself with new instruments to tackle these weaknesses.

Indeed, significant reforms have been adopted since 2010 to increase the resilience of the euro area. At the European level, the revamp of the Stability and Growth Pact and the creation of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) strengthened the fiscal framework and the crisis management capacity with a permanent funding instrument. Moreover, the decision to establish the Banking Union in 2012 has put in place the basis for a supranational supervision and crisis management. Also at country level, steps were taken to correct macroeconomic imbalances, including through the implementation of structural reforms.

These measures have put the euro area on a more resilient and safer footing and we have started to see the pay-off: countries with previously large current account deficits now record surpluses, competitiveness has improved and the impact of reforms on growth starts to be visible in some countries. At the same time, these positive developments should not lead to complacency as crucial challenges remain in an environment of low trend growth and still high debt levels in a number of euro area countries. To address these challenges we need to continue to make progress at national and European levels. At the national level, the reform momentum needs to be maintained while at the European level, further steps need to be taken to complete the institutional architecture.

Let me start by reviewing a few facts on the euro area recovery and on the adjustment process during the past years.

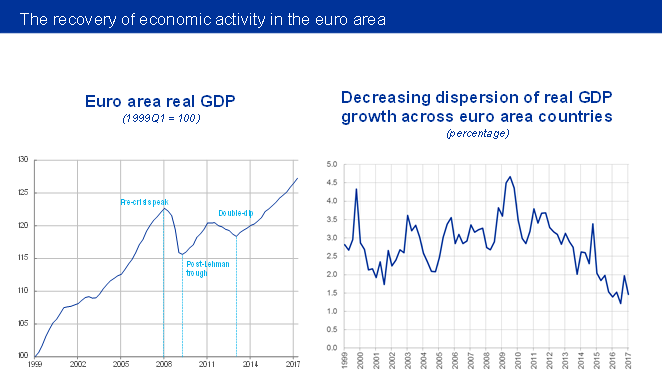

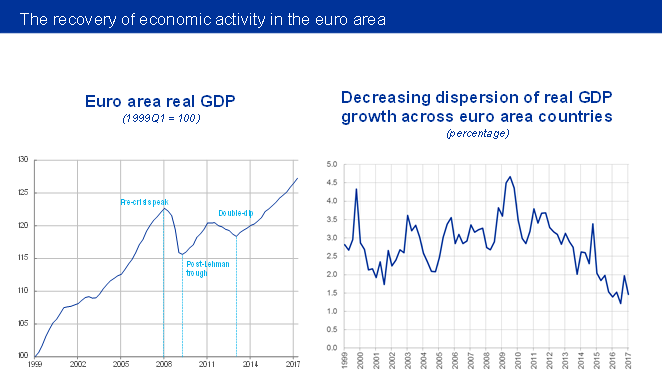

The euro area has been on a recovery path during the past four years (see slide 1, chart on the left) with the recovery gaining momentum as of late. The euro area has finally reached a GDP level above the 2007 level, recovering the output lost over the period 2008-2013. On the other hand, stronger growth was coupled with increased convergence of growth rates in the euro area, as shown by the development of the cross-country standard deviation of annual real GDP growth over time (see slide 1, chart on the right).

Slide 1

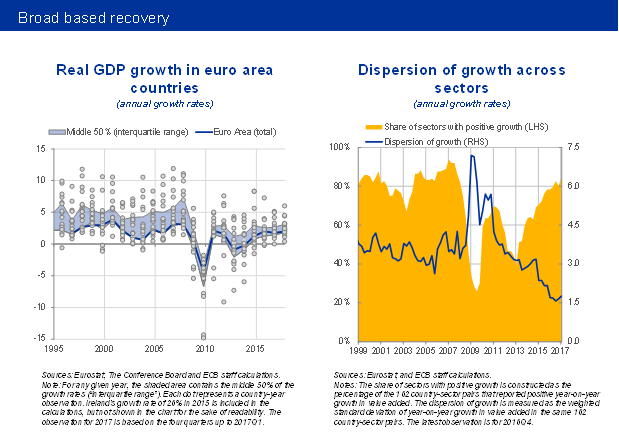

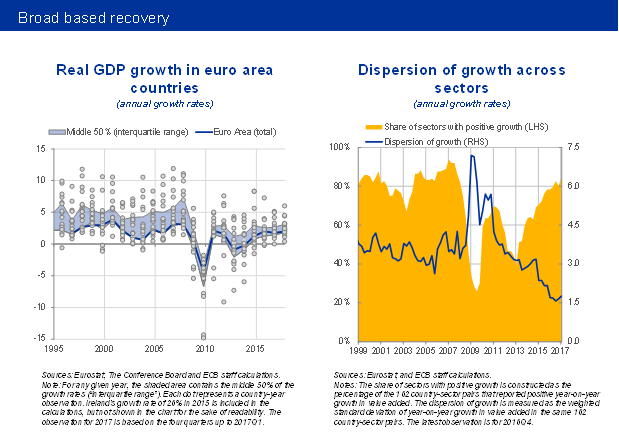

Over recent quarters, the economic recovery has also become more broad-based across euro area countries and the different sectors of the economy. All euro area countries are currently recording positive real GDP growth in annual terms, for the first time since 2007 (see slide 2, chart on the left). At the same time, growth rates have become less dispersed across countries compared to the past, which also suggests increased business cycle synchronisation within the euro area.

The recovery is also broadening across sectors. The share of sectors with positive growth has returned to its pre-crisis levels (see slide 2, chart on the right). At the same time, the dispersion of growth rates across sectors is the lowest since the inception of the euro.

Taken together, the broadening of the recovery across countries and sectors suggests that it has not only gained momentum but, importantly, the recovery has gained robustness.

Slide 2

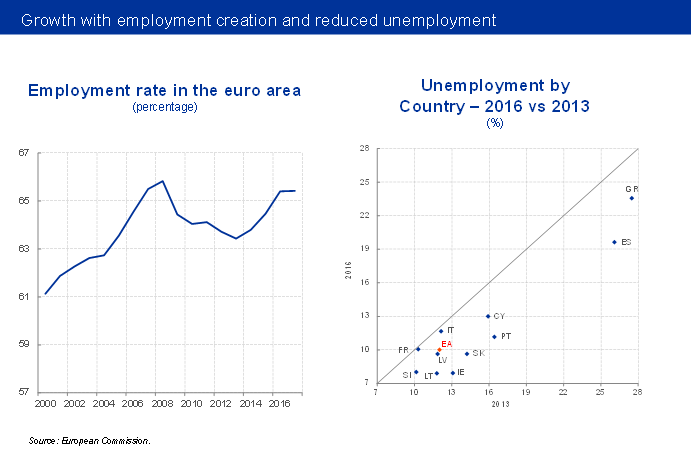

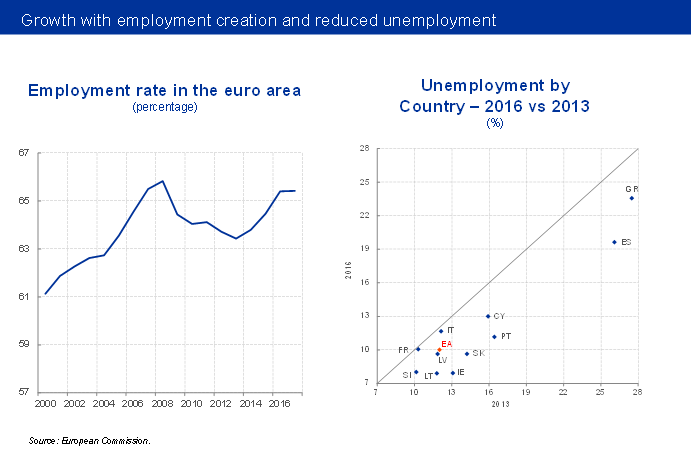

A more robust recovery has also been visible in the labour market where conditions have improved markedly (see slide 3, chart on the left). Employment has risen by almost 6 million since 2013. This stands in contrast to the jobless recovery of 2010, which is another indication of the turning tides in the euro area.

Furthermore, labour market recovery is stronger in countries where it was especially weak. Euro area unemployment rate has receded, despite still too high unemployment rates in some countries (see slide 3, chart on the right).

Slide 3

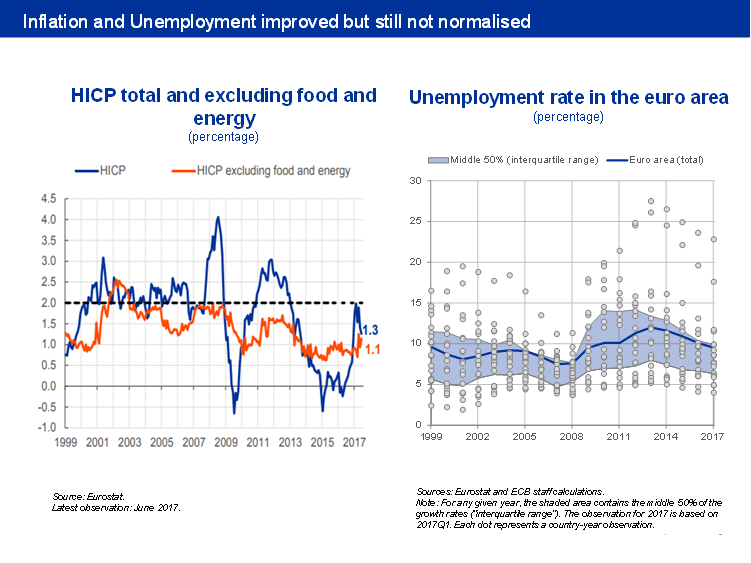

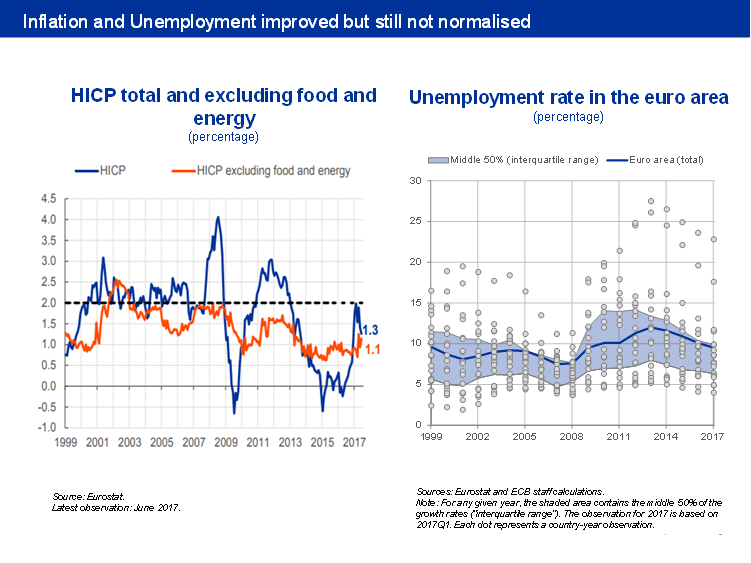

Notwithstanding these improvements, the growing uncertainty surrounding the strength of the world economic recovery, and of the US in particular, makes the normalisation of inflation and unemployment levels in the euro area more difficult (see slide 4).

Slide 4

Adjustment and resilience

The increased robustness of the euro area economy is also reflected in the gradual unwinding of the macroeconomic imbalances accumulated before the crisis. In fact, countries that eventually entered a programme had recorded large losses in price competitiveness in the run-up to the crisis. Since the crisis, the initial dramatic increases in the real exchange rates of those countries have largely been corrected (see slide 5) along with a marked improvement in price competitiveness. In most programme countries relative unit labour costs are now below their respective level in 1999.

Slide 5

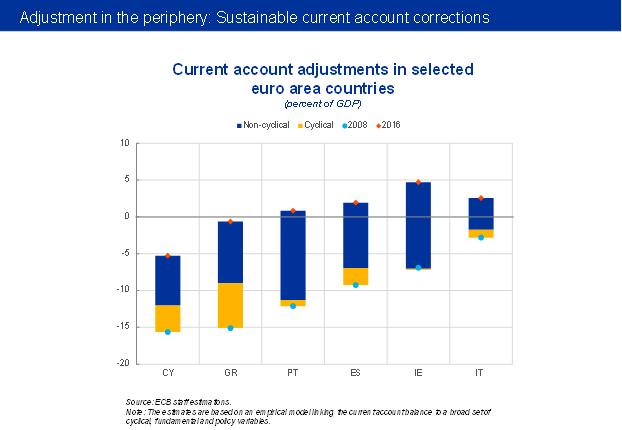

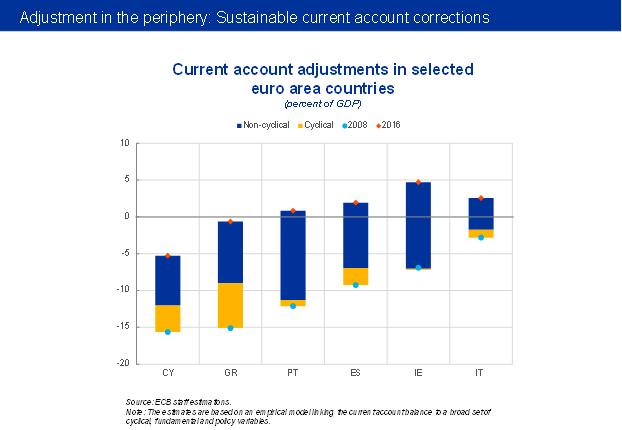

At the same time, the large current account deficits registered in several euro area countries before the crisis have narrowed significantly or even turned into surpluses (see slide 6). Importantly, the largest part of the current account adjustments is estimated to be non-cyclical and therefore likely to be sustained as the recovery continues.[1] From this perspective, it is very relevant that (with the exception of Greece) the external account improvements were also a consequence of dynamic export growth and not just resulting from import compression due to the recessionary period.

Slide 6

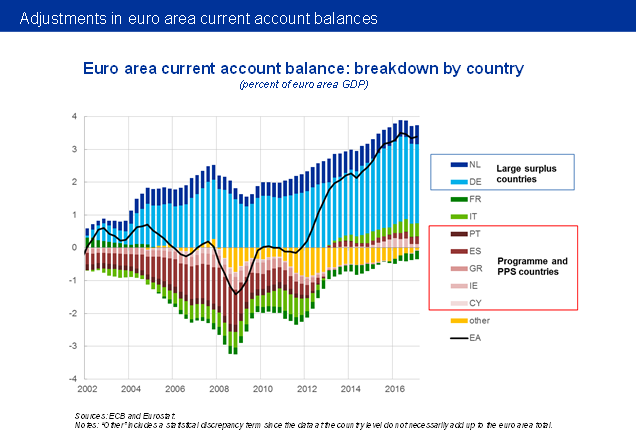

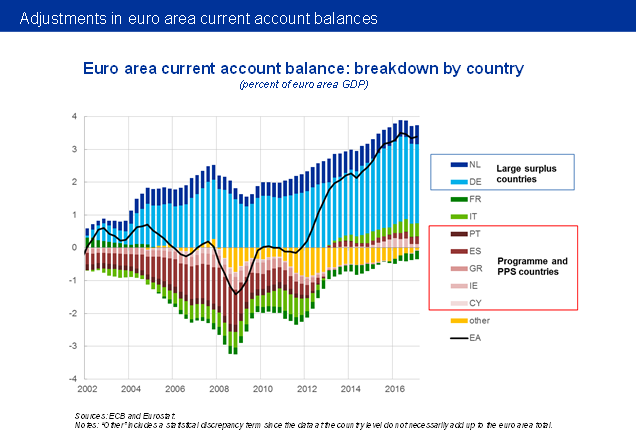

The impressive correction of current account deficits in some euro area countries has been mirrored in a significant adjustment of intra-euro area trade and current account imbalances (see slide 7). As a result, some euro area countries with large external surpluses now record current account surpluses mostly vis-à-vis countries outside the euro area.

Slide 7

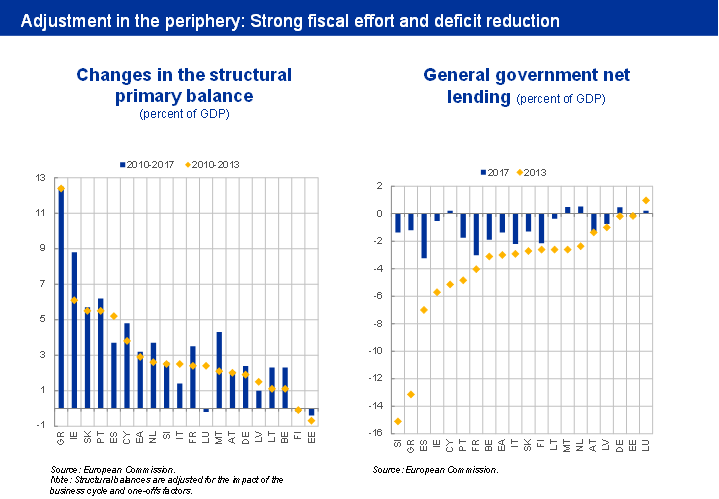

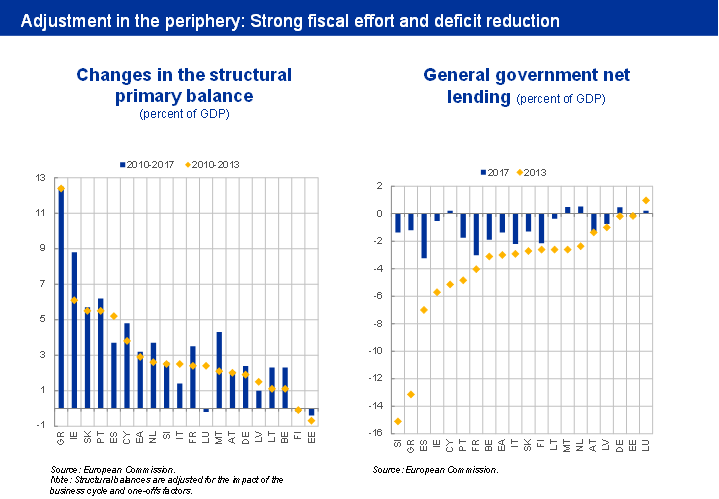

Fiscal deficits have been reduced. Fiscal effort, measured as the change in the structural primary balance, has been significant in many countries (see slide 8, chart on the left). As a result, and also thanks to the reduction in interest payments, fiscal deficits are now in almost all countries below 3% of GDP (see slide 8, chart on the right).

Slide 8

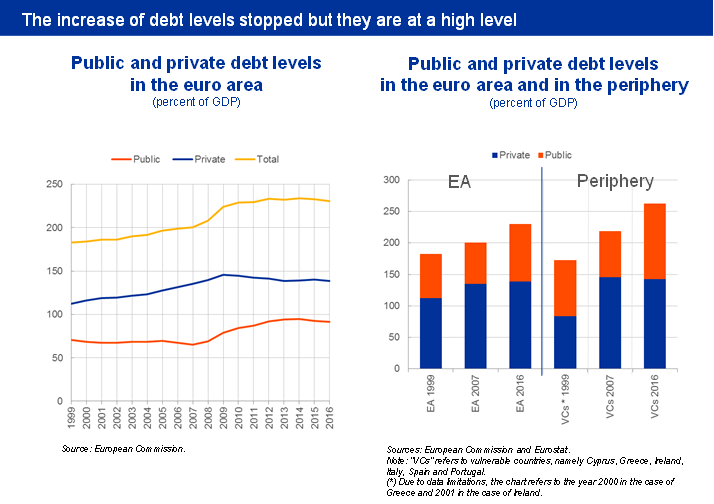

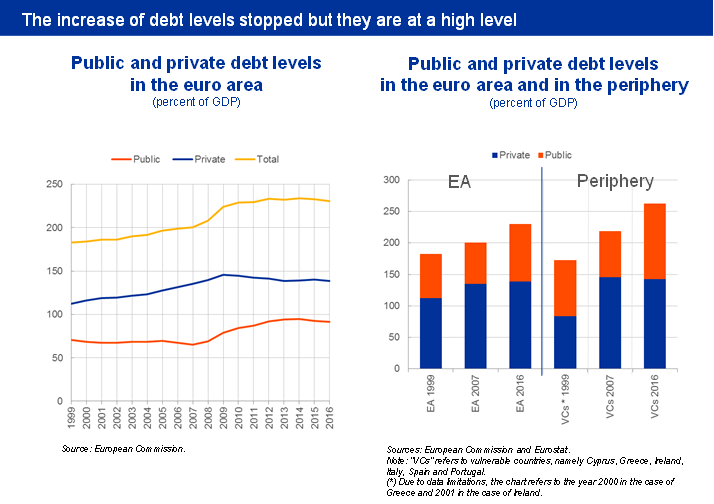

Beyond fiscal deficits, the level of public and private debt has also posed concerns in some countries. In the run-up to the crisis, it was not so much public debt but rather the private sector indebtedness that increased substantially (see slide 9). This should be underlined because, as Jordà, Schularik and Taylor (2016) said: “…private credit booms, not public borrowing or the level of public debt, tend to be the main precursors of financial instability in industrial countries.” [2]

It was only after the crisis that public debt increased, on account of the necessary interventions. More recently, both public and private sector debt levels stabilised, thanks to consolidation efforts and private sector deleveraging, even if remaining rather diverse across countries.

Focusing on the programme and post programme countries, private debt levels in percent of GDP are currently lower than 10 years ago in Spain, Portugal and Greece, but still higher in Cyprus and Ireland. Public debt however is higher than at the start of the crisis, across the euro area. Increasing the growth potential of euro area economies would help to achieve a downward shift in the debt-to-GDP ratios.

Slide 9

Synchronisation of economic cycles and symmetric shocks

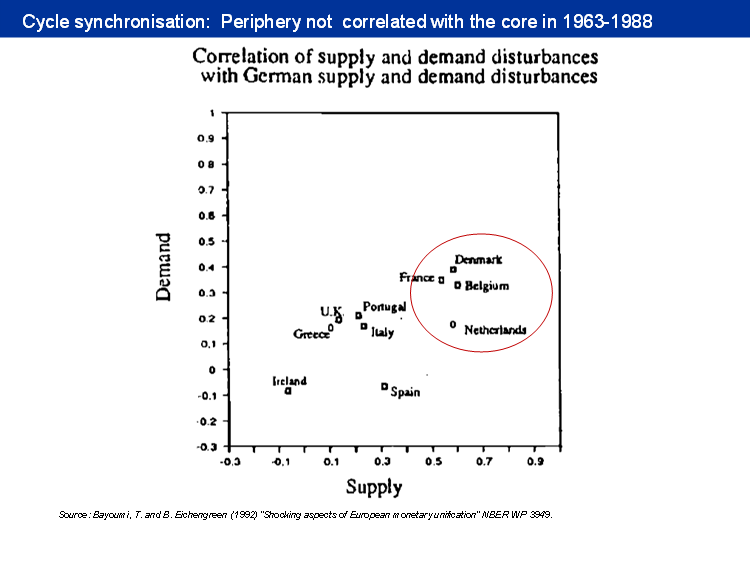

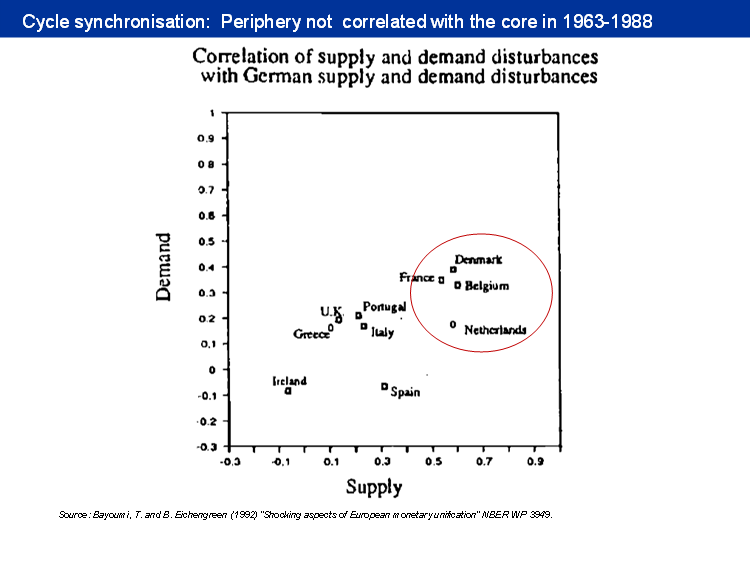

An important aspect stemming from the theory of optimal currency areas, relates to the risk of asymmetric shocks to countries in a monetary union, placing them in different phases of the economic cycle, which would make a single monetary policy inadequate for a smooth functioning of the union. This concern was in everyone’s mind when the EMU was being conceived. In 1992, Bayoumi and Eichengreen published a well-known paper,[3] using data from 1963 to 1988 to calculate the correlation of demand and supply shocks of each potential EMU member with Germany, which represented the core of the union in terms of size and level of development. The analysis clearly identified a core of countries well correlated with Germany and a periphery much less correlated to the centre (see slide 10). They also showed that the difference between core and periphery was bigger than the one among the Federal Reserve Regions in the US.

Slide 10

This analysis raised concern of whether EMU could face the problem of asymmetric shocks thus hampering the single currency performance. Some other authors[4] pointed nevertheless to the fact that synchronisation could be endogenous to the formation of the monetary union itself, meaning that the adjustment to the single monetary policy would lead member countries’ cycles to become more aligned.

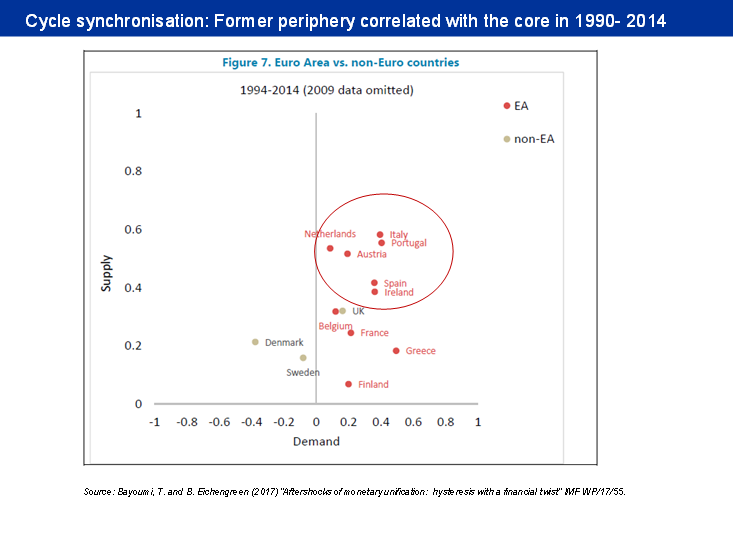

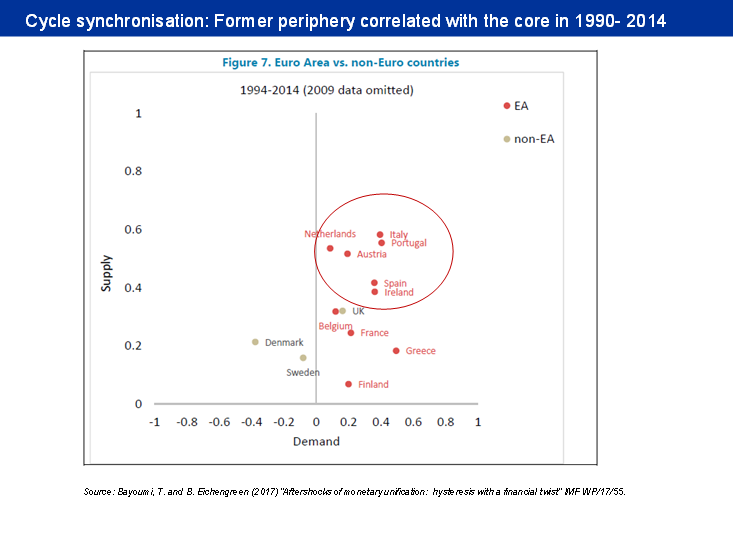

Interestingly, this is precisely what Bayoumi and Eichengreen found out when conducting the same analysis in 2017, with data from 1990 to 2014. Remarkably, most of the countries (with the exception of Greece) that were previously in the periphery are now more correlated with Germany than some of its own neighbours (see slide 11). From this point of view (synchronisation of cycles) there is now a new core in the euro area to which most of the geographically periphery now belongs.

Slide 11

This is particularly important as a sign of robustness of the euro area, indicating that all countries were able to restore competitiveness within the euro and return to growth thus ensuring a better transmission of the single monetary policy. The euro area is now better prepared to withstand financial market shocks.

Future risks and challenges

These signs of recovery and resilience should not lead to any complacency towards the future of the euro area. Besides the tasks of normalising inflation and reducing unemployment to more acceptable levels in all countries, many structural and institutional reforms are needed to safeguard and improve the future functioning of the euro area. Both the Five Presidents Report on “Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union” (2015) and the recent EU Commission paper on the “Deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union” (2017), provide sufficient guidance on the way to proceed. Next steps include: completing the Banking Union, creating a Capital Markets Union, creating a Macroeconomic Stabilisation function at the euro area level, possibly with a European Treasury and a full European Monetary Fund. These institutional reforms would be crucial for the EMU to face two of the most fundamental objectives to consolidate its future: increase its growth potential and restore a path of real economic convergence among its member countries.

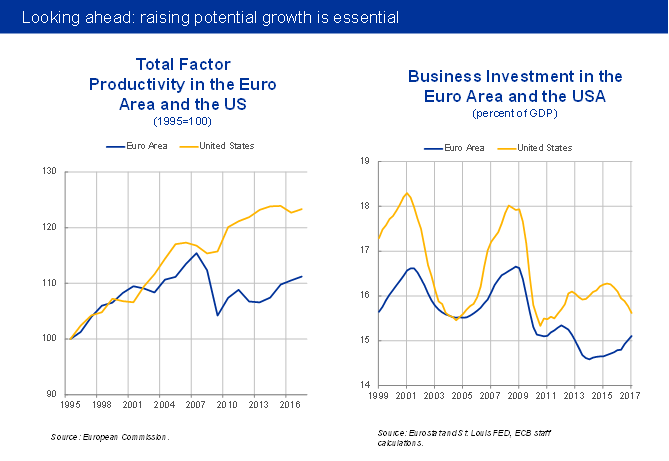

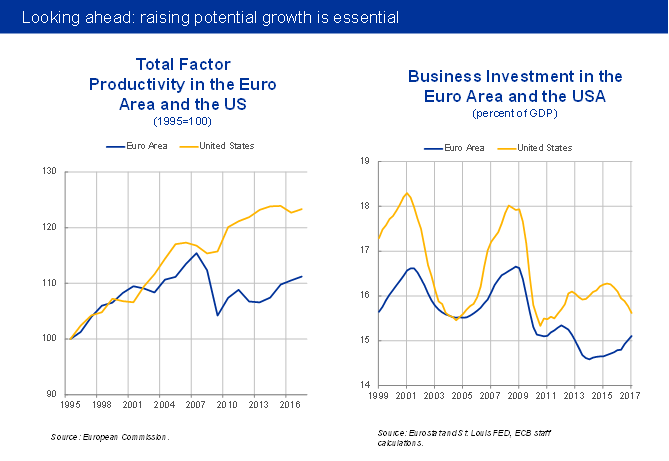

While at present the recovery is on track, looking ahead the growth potential of euro area economies needs to be strengthened. Further efforts thus need to be devoted to strengthening productivity growth which requires an expansion of productive investments. Both the recovery of productivity and that of business investments in the euro area has been lagging behind that of the US (see slide 12).

Slide 12

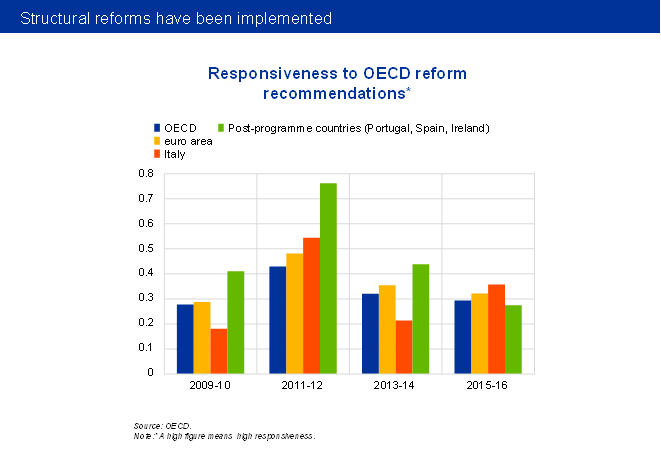

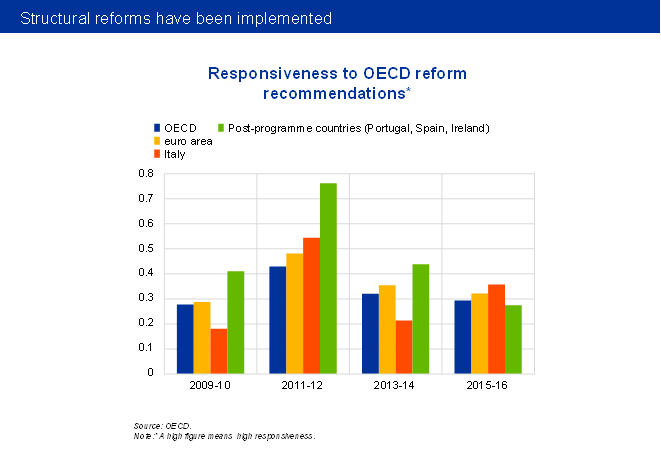

There have been important reform efforts in the euro area in recent years supporting the recovery of potential growth. Since 2009 the reform responsiveness in the euro area has exceeded the OECD average (see slide 13). In particular, countries which had financial assistance programmes took a number of reforms to improve their resilience and competitiveness, in particular through reforms in product market regulation, employment protection and wage flexibility, and through revamping of active labour market programmes. Many of these reforms are expected to support potential growth but they tend to exert their full impact with a considerable lag.

At the same time, the business environment in some of the euro area countries is still well behind that of countries near the frontier, and reform needs are significant.

Slide 13

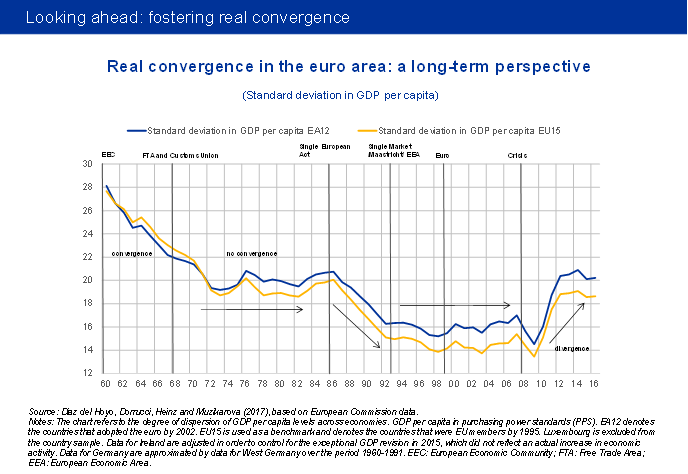

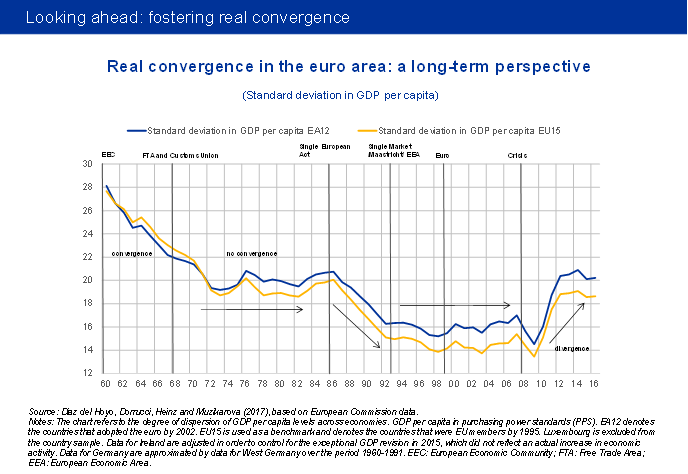

A final challenge relates to convergence of income levels in the euro area. Gradual but real economic convergence of income per capita across all countries is the ultimate condition for a healthy and consolidated economic and monetary union prepared to resist the test of time.

Taking a long-term perspective[5] – from 1960 till today – and focusing on the twelve initial members of the euro area, it is striking that the euro area crisis (2010-13) was the only period when strong divergence materialised in the dispersion of GDP per capita levels.

However, it is since about 1993 – well before the adoption of the euro – that this group of countries does not experience phases of marked income convergence, such as those recorded in the periods 1960-1972 and 1986-1992. The same applies to broader groupings of mature economies in the European Union, such as the Member States which had joined the EU by 1995 (see slide 14).

Focusing on the individual euro area countries with the greatest catching-up needs, while some have made significant progress, others have stalled or even reversed their process of real convergence. Such countries are concentrated in the South of Europe, with Greece and Italy being the two most prominent examples.

Slide 14

The re-establishment of a path towards real convergence in the euro area is, therefore, a vital and difficult challenge. Some tentative signs of reversal of the divergence experienced during the euro area crisis are visible since 2014. But more needs to be done, along the lines sketched in the Five Presidents Report and the Commission paper already mentioned. Also crucial in this regard will be the enhancement of countries’ economic structures through improved institutions and governance.

Let me conclude. It is clear that the euro area recovery is becoming increasingly robust. The upturn is not only strengthening and broadening, but is also starting to rest on more solid structural foundations. The daunting challenges ahead may still have an existential nature but they can be overcome with time. However, the wise attitude now is not to predict the future but to prepare it.